If the term interoperability doesn’t turn you on, it’s not surprising. But the time has come to champion changes to this important issue

Interoperability, or more precisely our healthcare system’s lack of it, costs an average GP about $57,000 a year in lost income.

Most GPs aren’t convinced they know what is meant by the term. If you ask, you’ll get something reasonably sensible in response such as “how our practice talks to specialists, pathology and allied health … how we get test results”.

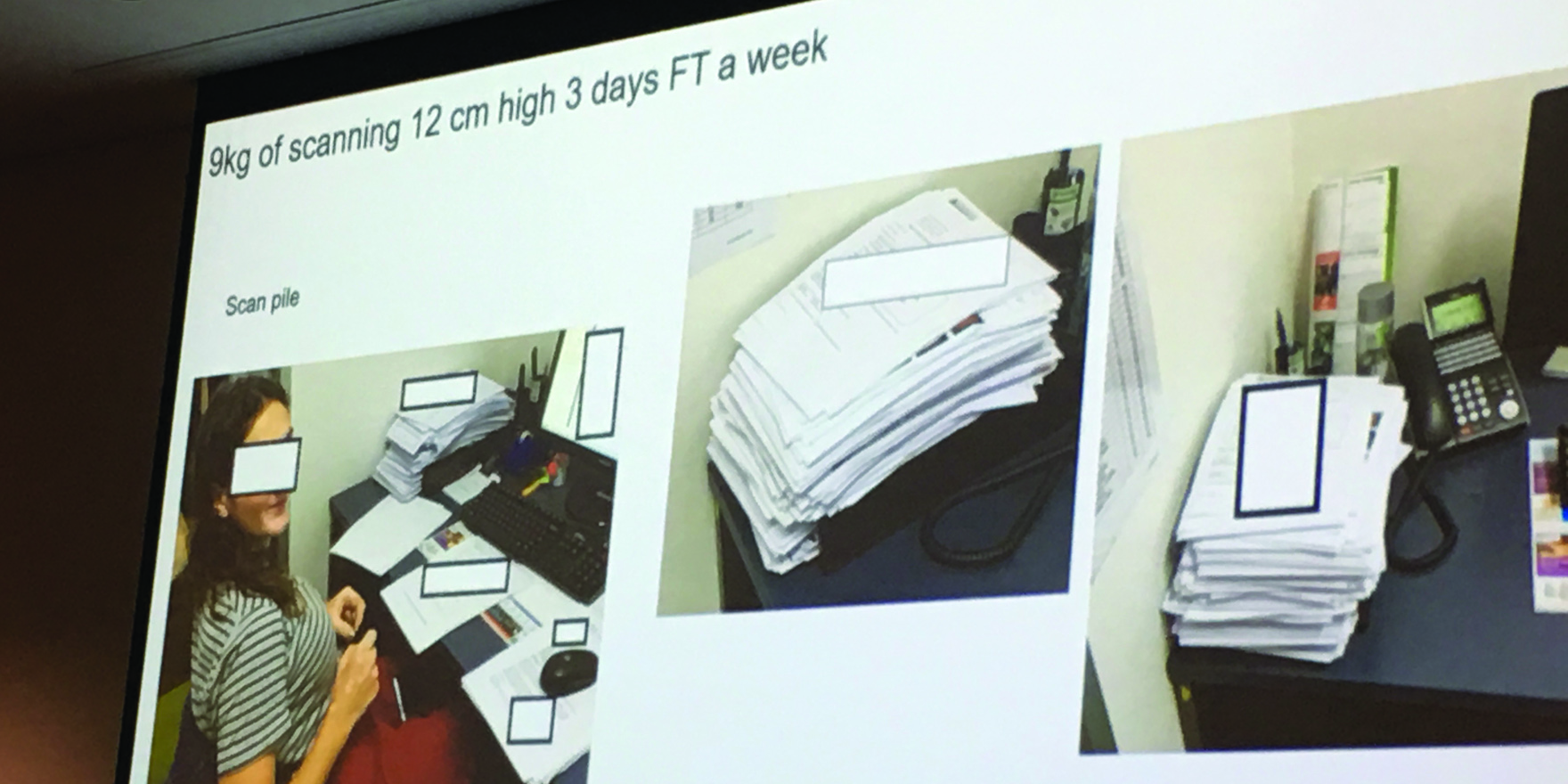

The fact many practices still have piles of paper building up near their fax machine, and PDF documents falling off the end of the printer, and staff still spend time processing paper into desktop patient management systems, continues to raise concerns among practice managers and owners. Yet, interoperability does not generally worry most GPs.

It is as interesting, it seems, to a GP as the idea of superannuation is to a millennial. The parallel is relevant. A millennial’s lack of interest in their super can cost them hundreds of thousands of dollars by the time they retire. For GPs, interoperability can cost them up to 20% in lost income each year.

If you amortise that, even over the time of the MBS freeze, you’re talking a lot of money.

There’s another reason there should be more rage and engagement here. GPs care about their patients first, and safety is a day-to-day issue. Interoperability is firstly a patient safety and servicing issue, and secondly an income issue.

Yet we still have something akin to “out of sight, out of mind” (except for those pesky paper mountains). What is going on?

It’s complex. But here are a few ideas on why GPs might feel so helpless they can’t waste their time caring. Not yet anyway.

1. Out of sight out of mind

Interoperability occurs mostly outside the day-to-day remit. It’s hidden in patient management systems and how those talk to the outside world. Most GPs would assert that even if they did fully understand what was going on, how could they possibly intervene to help? After all, how does a GP affect how a message is sent from their patient management system, or even the fax, once it has left the surgery? Or how do they affect how it comes back to their practice? It’s largely out of their hands, isn’t it?

2. It’s technology, not medicine

How systems exchange data securely and seamlessly is a technology problem. And a complex one. How could a GP possibly influence how that world evolves around them?

3. It’s mostly in hands of private enterprise

The cut and thrust of the various interoperability vendors has created a situation where most of their systems won’t talk to each other, each hoping to gain eventual market dominance by doing this. How could a GP hope to influence these dynamics?

4. It’s not costing us anything right now

Mostly, GPs don’t pay anything for the vast array of systems of messaging and communication, once a message or data leaves their office. This is despite them being the major hub of data exchange and communication in the whole healthcare system. If they aren’t paying, there is obviously going to be less concern over how efficient or inefficient messaging and communications are. There are no signals or reason to make it more efficient because there is currently no cost. And hopefully for them, no future cost.

5. It’s complicated and can be dull

Even with the promise of an additional hour a day in efficiency, if we could get interoperability right – that’s one hour to make another $57,000 or so, or relax a bit more – I’ve lost readers. Because it seems too complex and far way.

But like superannuation, just a little bit of time spent understanding and organising, might result in hugely significant changes in the coming years.

Here’s why GPs might have some reason to get organised on this issue. Angry even.

The time has arrived where all the technical issues around interoperability are sorted. If you could wave a magic wand and sort out the issues around vested interests fighting and jockeying for position, interoperability in our primary healthcare system could be significantly sorted within about 12 to 18 months. That $57,000 is much closer than you think. And so are concurrent improvements to patient safety and servicing as well.

It’s mostly a matter of getting all the vested interests all pulling in the same direction to get this issue sorted.

The current situation is that the job has been prioritised by the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA) – the same group that is running the MyHealthRecord project . The ADHA has done a lot in a short amount of time to attempt to rally the various interested parties and get some agreement among those interests to sort out this issue.

In a meeting last week at HISA’s annual innovation conference in Brisbane, many of these parties met to assess the progress and discuss current road blocks. There are two key breakthroughs the ADHA may have managed:

• The agency has apparently convinced the secure messaging providers, which previously spent much effort thwarting the attempts of each other to gain market share by preventing communication happening seamlessly and protecting their own suppliers, to “burn their boats”, come to the centre for the greater good, and agree to a protocol to talk to each other.

• The agency has opened a crack in the hold private pathology providers, mainly Sonic and Primary Health Care, have on most GP messaging, by convincing them to start providing pathology results to the MyHR.

These are giant steps. But they are steps which can easily be unwound. None of the steps is locked in by law or regulation, as many think they should be. That’s probably because there is so much at stake commercially, and if you upset some of these companies, particularly the pathology groups, repercussions can occur elsewhere in thr system.

The secure messaging providers and the pathology labs still have very strong commercial imperatives not to co-operate. They are likely to feel the need to keep the process slow and to make sure they are positioning themselves well. And if the ADHA is to succeed in its ambition, there will be losers. So there is a long way to go.

This is where GPs come in. Although there is support in the peak bodies for all these initiatives – The RACGP and the AMA are backing the ADHA and providing resources to help – grassroots GPs aren’t engaged in this battle.

If these GPs get themselves organised and educated on this is vital issue they would make a powerful voice that all the private parties in play here could not afford to ignore.

If grassroots GPs do engage, if they make it very clear to the pathology labs, patient management system vendors, the government, and the secure messaging vendors, that if they don’t ensure interoperability is optimal and seamless for them – the chief users of the system – then there will be repercussions.

Interoperability is one of the key topics at The Medical Republic’s Wild Health Summit No 1: Connectivity, to be held at Belvoir St Theatre on October 16. Key speakers will include: Dr Zoran Bolevich, CEO of e-Health NSW; Tom Bowden, CEO of Healthlink, a major private secure messaging providers; Dr Ged Foley, CEO of IPN, which has more than 2000 GPs; and Matthey Galletto, CEO and founder of MediRecords, the first cloud-based patient management system vendor in Australia. GPs can use the code WILDTMR and quote their AHPRA number to get a 20% ticket discount. For any queries, email: jeremy@medicalrepublic.com.au