A recent Elsevier expert panel webinar agreed that the pandemic is creating momentum to properly use this underestimated sector of the health workforce.

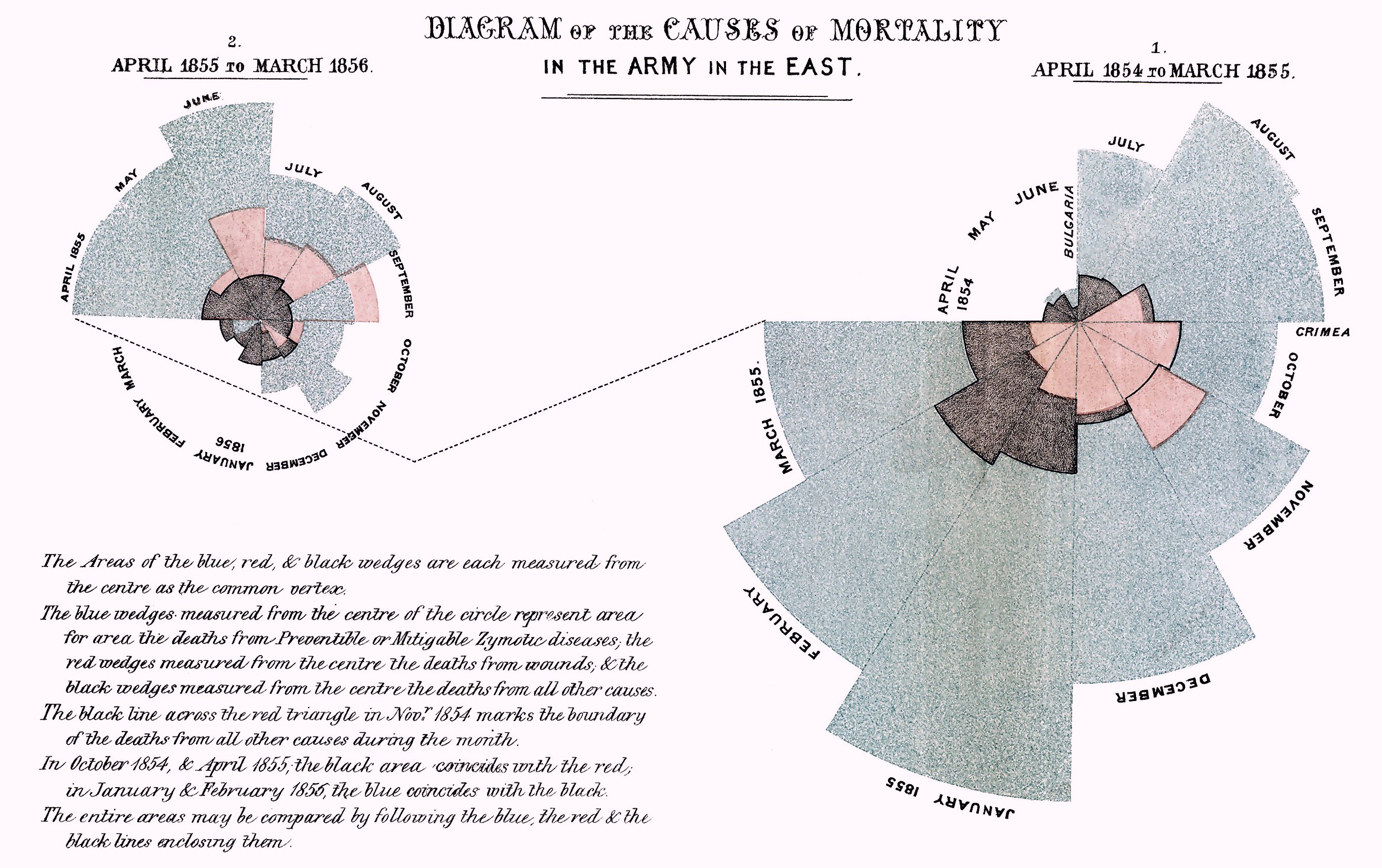

When Florence Nightingale stepped into Scutari military hospital in Constantinople (Istanbul) in 1856 to assist with the Crimean war effort she was met with a scene of chaos.

The incompetence of the British generals – most famous for the folly of the “Charge of the Light Brigade” – resulted in very high numbers of wounded on the battlefield. But the issue was woefully compounded by the mortality rate of wounded soldiers once they arrived at the hospital.

Nightingale soon calculated that mortality rate at the British military hospital was five-fold worse than that of a normal hospital for the types of injuries the patients had sustained. She quickly established a means of recording important data around the hospital’s overcrowding, ventilation, drainage, sanitary procedures and comforts.

She established an evidence base for arguing with a hostile military establishment and won arguments for improvements through data collection and analytics. She was our first Chief Clinical Information Officer (CCIO, this despite her being a nurse, not a doctor.)

Today, COVID-19 might represent the kind of stressor on the system that the Crimean war did for Nightingale in 1856. Conditions imposed by the pandemic are reframing how we view frontline hospital resourcing and management, in particular informatics and nursing.

Nurses have vastly increased their profile as frontline lifesavers during COVID-19, as they have had to step up to significantly more clinical responsibility as a result of doctor resourcing pressure.

They’ve been placed in the middle of a complex and a rapidly evolving digital healthcare-delivery environment.

In many situations in this crisis, they have stepped into roles that hospital managers might not normally have ever put them in, and they’ve proven that they are an underestimated and underutilised healthcare system resource.

COVID-19 has provided hard evidence that nurses can move upstream into more complex roles in clinical care.

One area where this effect seems to have been profound is in the management of clinical informatics.

In a survey conducted recently by Elsevier during an expert panel on The Future of Healthcare webinar series, asking what the key changes in nursing in the next two years might result from COVID-19, 52% of the audience felt that nursing informatics would be the biggest area of change. This was followed by a requirement for a new framework in which nurses practice and are educated.

Karen Blake, head of clinical informatics for healthAlliance in New Zealand – a group that manages nearly 40% of the population in that country – told the panel that her clinical informatics background was critical in the effectiveness of her group’s COVID-19 response.

“A key part of my job is around working on interoperability, getting disparate systems to work together and sharing data and information across different systems and groups,” she said.

“[During COVID-19] within the first week of mobilisation, we launched and completed a really large project to share information more effectively between hospitals and primary care.”

In both Australia and New Zealand, despite big strides in the last few years in hospital-based informatics, you have to be a doctor to earn the title of CCIO. Nurses can be Chief Nursing and Midwife Information Officer (CNMIO), or something equivalent which is generally viewed as a less holistic role. The expert panel saw no reason why nurses can’t and should not be CCIOs in the future in Australia and New Zealand.

Kate Renzenbrink, CNMIO with Bendigo Health, told the webinar that while there were 25 nurses with her equivalent qualification and that the specialisation was on the rise, digital informatics in tertiary care tended to be dominated by doctors.

She said COVID-19 had likely opened people’s eyes to the ability of nurses to take more responsibility in “connecting care seamlessly and following a patient so that they can move through a system with the right information that goes to the right people at the right time”.

Ms Renzenbrink said that in educating nurses there were definitely more pathways than there had been in the past but, as ever, funding remained an issue, even in developed economies.

“I think there’s much more interest in collaboration with [new] models of care… and how we can we open up career pathways in all sorts of nursing specialties,” she said.

Ms Blake said that while COVID-19 had accelerated the pace of change in how nurses were viewed in a fast evolving healthcare ecosystem, the profession would need to take the lead if there was to be sustainable and meaningful change.

“We have responsibility as a profession to sustain and maintain [these COVID-induced changes] into the future,” she told the expert panel.

“One of the challenges that we’ve got in the future as we become a more digitised workforce is how do we start enabling our existing workforce to really embrace new ways of working? For people that get into informatics, that it’s a really exciting profession.”

Outside of informatics, experts are generally predicting that COVID-19 will lead to a surge in a requirement for nurses in a workforce that is already not meeting demand.

Dr Mary Glasgow, the Dean of Nursing at Duquesne University in the US believes that COVID-19 will lead to the biggest surge in the requirements for nurses in the country since the 1970s.

But, on the Elsevier expert panel survey, she said that in a post-COVID world, there would need to be a new context for how nurses were educated and employed.

One important challenge, Dr Glasgow said, was “getting more clinical experience to our students”.

Dr Glasgow said that additional clinical education and support resources were contributing factors as to why more nurses weren’t working in hospital settings today.

Ms Blake believes that New Zealand is likely to have a surge in people wanting to do nursing as a result of COVID, too.

“In New Zealand, we’ve seen really high rates of applications for people wanting to join our police force to the point where they’ve just had to close all registrations, and I suspect that we’re going to start seeing the same thing in nursing and midwifery,” she said.

“As we see other industries like tourism and hospitality and the retail sector absolutely decimated, and we’re only at the beginning of a recession, people will start looking towards more secure forms of employment.”

A recent World Health Organisation report suggests nursing numbers remain well below the required number, before you even start thinking about needs induced by a global pandemic.

The State of the World’s Nursing Report 2020, published in April, estimates there was a global shortage of 5.9 million nurses in 2018, and things aren’t improving.

The report urges governments to invest in the rapid acceleration of nursing education, apart from anything else to respond to changing technologies and new models of integrated health and social care, and to “strengthen nurse leadership to ensure that nurses have an influential role in forming health policy and decision-making, and contribute to the effectiveness of health and social care systems”.

It’s a position that the Elsevier panel was significantly aligned on.

Ms Blake emphasised that we need to have nurses working more tightly alongside both clinicians and allied healthcare professionals “in a collaborative interdisciplinary way”.

Ms Renzenbrink believes nursing informatics has a place now as its own nursing speciality but says that in Australia the profession’s leaders will need to better track and understand the roles of the existing specialists if they are to leverage them in better education and training moving forward.

She said that in order to build workforce capability it would be important for nursing leaders to identify the issues that COVID has thrown up so they could address the new workforce issues for the profession.

If you would like to receive a copy of “The Future of Healthcare” insights report, please register your interest HERE.