What does it say if the MyHR project is not agile enough to pivot around a game changing and locally developed technology such as FHIR?

What does it say if the My Health Record project is not agile enough to pivot around a game changing and locally developed technology such as FHIR?

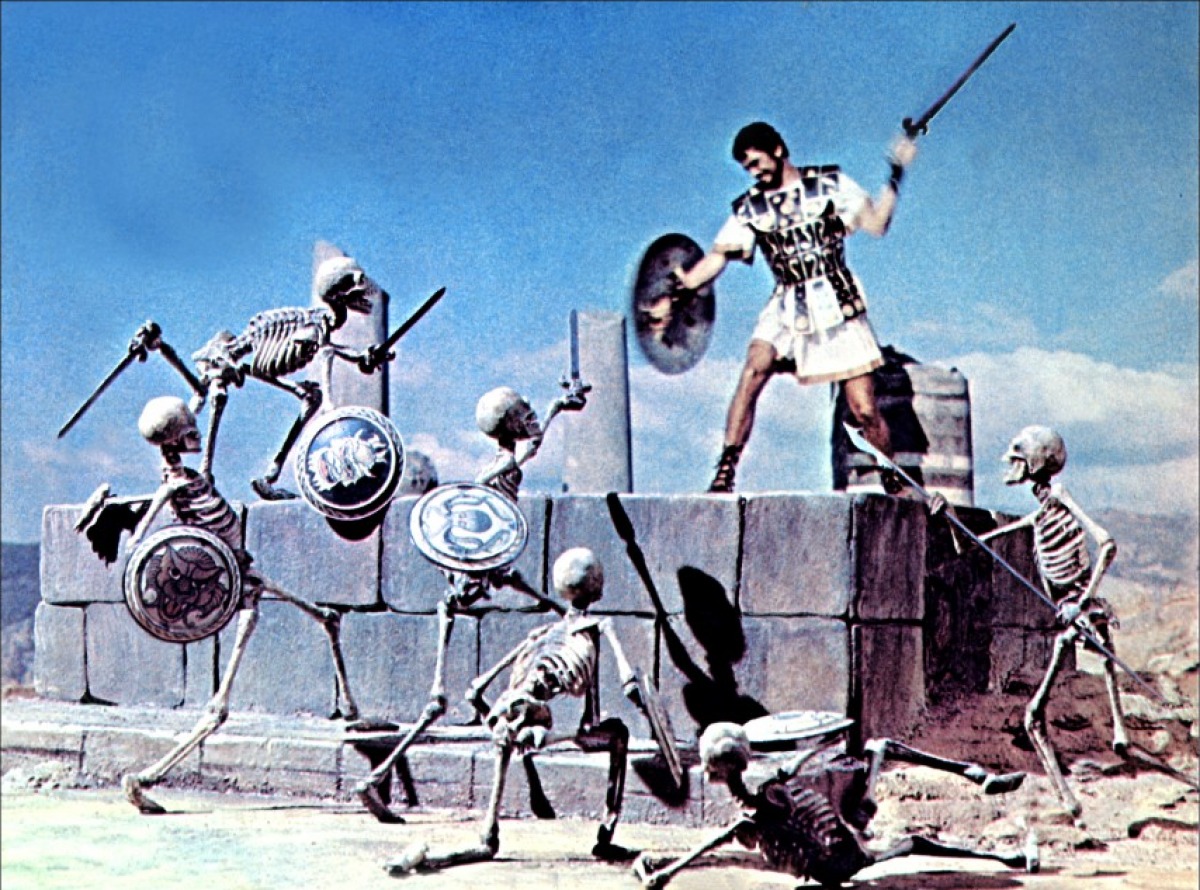

My favourite Saturday night movie as a kid was Jason and the Argonauts. It’s a story sourced from Greek mythology about a hero, Jason, who leads a band of intrepid outcast adventurers across the oceans and into battles with the likes of giant bronze statues that come to life, skeleton armies, and seven-headed snakes, in a quest to obtain the fabled golden fleece.

The fleece has magical healing powers and holds the key to Jason rallying the people of Thessaly to take back the throne and deliver his people from oppression. Unbeknown to Jason, he has been sent on his deadly fleece endeavour by the King of Thessaly who hopes Jason will perish on the mission.

After penning a controversial blog on the My Health Record just a few weeks back, and one or two more since, global health informatics expert and the enigmatic inventor of a new global health interoperability standard, Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR), Grahame Grieve, is suddenly looking a lot like Jason. And Tim Kelsey, the head of the Australian Digital Health Agency (ADHA), at a stretch, maybe like the King of Thessaly. (OK, too far, Kelsey is definitely not that character but let’s go with it for the story’s sake).

Grieve, who also had to travel to foreign lands to seek his destiny – the US mostly, where FHIR and his talents have been welcomed, nurtured and encouraged – announced in his blog a couple of weeks back that the US-based Argonaut project would be coming to Australia via major global EMR vendor Cerner. Yes, Grahame and the Argonauts are returning home with FHIR.

The announcement has huge implications for the Australian digital healthcare scene and with that for the mid-term future of GP digital communications. Grieve’s FHIR solution is fundamentally different to the solution that the My Health Record is currently being built on. And the difference is worth everyone stopping and thinking about.

The My Health Record began life with a set of goals for which the most obvious architecture solution at the time was something called Clinical Document Architecture (CDA). Grieve, who worked extensively on the pre-cursor to the MyHR, the PCEHR, even agreed with this initial approach. But as the PCEHR project proceeded, Grieve found himself compelled to explore other solutions as he found, increasingly, that CDA and how it was being used, was never going to be able to achieve the original goals of the project.

The MyHR implementation of CDA relies on healthcare providers, such as GPs, pushing documents (usually PDFs) to a central repository. The problem with this, says Grieve, is that there is no relationship between the documents and no way to reconcile information between the documents.

Each PDF is a discrete piece of information which makes the whole system highly inflexible.

The issues he had with CDA led him to start developing an alternative and more-flexible solution, FHIR.

FHIR is an open architecture which makes the data in systems such as the MyHR available to be pulled on demand in accordance with specific requests and in synch with data being held on local systems, such as apps or patient management databases. It is open and allows others to reach into distributed data securely, on demand, when needed, while the CDA solution in the MyHR is a central repository of data stored in a format that is hard to sort and analyse.

Grieve’s little side project wasn’t a hit with NEHTA (now ADHA) at the time. Especially when it started to garner a lot of interest from some big overseas vendors, who were struggling with the very same architecture and standards problems that NEHTA and Grieve were, between CDA and another related standards technology, HL7-2.

Big projects, especially big government projects aren’t easy to execute at the best of times. Grieve being off-reservation on the core of the MyHR architecture, even if it was his own personal project, wasn’t politically acceptable to the masters at NEHTA at the time and some pressure was brought to bear on Grieve to stop the side project.

But Grieve wouldn’t stop.

In the heady political world of giant IT transformation projects, especially high profile government ones, Grieve should have been eased out of the PCEHR project and never heard from again. But Grieve’s side project got a life of its own. He was eased out, but the big US-based EMR suppliers liked what he was doing and they encouraged him to keep going, funding some of his work.

On spec, FHIR beats CDA hands down. Its promise is for massive agility in the Australian digital ecosystem. More than anything, its promise is that data can be controlled at the patient end rather than centrally in a government warehouse.

And it appears to be very well thought of by local software vendors if this week’s Medical Software Industry Association Summit (MSIA) is anything to go by. It is even being built into some of the edges of the MyHR and looks likely to end up inside our major GP patient management systems over time. It’s hard to find someone who doesn’t like the utility of FHIR and see it’s potential.

As an example of on-demand and open access versus centrally stored, take the commonly used example of a patient arriving in an ED department and physicians having to react quickly under pressure.

As MyHR is today, the best the attending doctor might get is a prioritised medication list, which would be useful. Notably, this list has only just been added as a feature on the MyHR and much development work was needed for the MyHR to read and decipher the medication-based documents and then prioritise them. Even then, there are very real chances of inaccuracies based on where the data is coming from, who is uploading it, and how regularly it is being centrally uploaded.

Now take an open-architecture solution such as FHIR. The attending physician, having some idea of what’s going on with the patient, types a few specific things into his computer and a patient ID of some sort, that then polls variously connected and distributed primary care, allied health and hospital systems live. Only very specific and the most updated data is returned to the doctor.

Which of these alternatives would you prefer if you were that patient?

The FHIR story seems easy to interpret in hindsight. Why wouldn’t the ADHA and most other Australian vendors embrace this new standard and the open architecture approach, an approach which is now common in other markets which are moving fast in digital transformation?

It seems to be about timing and learning. NEHTA copped a lot of criticism for spending $1.2 billion and not getting far. There was a lot of political pressure being put on those running NEHTA to turn something that looked like it was a disaster into something more palatable.

Grieve will tell you that what NEHTA did was far from a disaster. “When you do something that big for the first time you don’t even really know what questions you are trying to answer until you get into the project,” he told The Medical Republic.

“ The technology was changing and we didn’t even know what was possible when we started. NEHTA, for all the criticism it copped, achieved enormous strides in our understanding of what is possible and how we should go there”.

But Grieve says that instead of learning, the pressure got to the government and they decided that the strategy and approach were right, it was just the execution that was wrong.

After thinking carefully about where NEHTA had gotten to, and the issues around continuing with CDA versus scrapping much of their work and returning to the drawing board with something like FHIR, the government opted to double down on CDA.

Grieve told The Medical Republic that the decision came as a huge surprise to most people in the know about interoperability and healthcare data standards at the time. He said that there was huge political pressure as NEHTA had spent almost $1.2 billion by then, had largely not made much tangible progress, and was under pressure to clean up what was becoming a potentially embarrassing political situation.

“NEHTA had to make expedient decisions, but we also learnt a lot,” Grieve told TMR. “We’ve seriously compounded those mistakes now, rather than taking important learnings and applying them.

“Yes, what we learned wasn’t pleasant. We were going down the wrong path and had to retrace our steps, and to some extent start anew.”

But by not apply our learnings, Grieve thinks we risk sacrificing generations of healthcare innovation and efficiency.

Grieve’s blog announcing the arrival of the Argonaut project, plants a stake in the ground for FHIR in Australia and must put some pressure on the ADHA and all local software vendors to think about how they move forward. Grieve, like Jason, has returned with the golden fleece.

Argonaut is a protocol that can be implanted in lots of e-health record systems and potentially allow much freer flow of information and better access control of what patients want and don’t want.

Cerner is mainly a hospital EMR vendor, so Argonaut and FHIR inside Cerner, will begin to spot FHIR capability inside hospitals all over the country over the coming years.

If FHIR takes off and the locals come to see its potential and utility, then they are likely to start getting restless very quickly about the MyHR CDA solution and why the ADHA is persisting with an architecture that may not be the best solution for the future of patient-centred communications and interoperability.

It would be very embarrassing if the Argonaut-based parts of the healthcare system in the future worked, as Grieve predicts, and the CDA parts don’t, or they don’t work well. Then heads might roll.

And now FHIR is here in a commercial product, some people are going to be forced to reconsider it. Others will surely wonder why they are building links to interoperability standards that don’t synchronise with the standards that have been adopted by the global vendors. That isn’t good for local business and must restrict their ability in the future to grow internationally.

Grieve says in his blog that the arrival of Argonaut is an opportunity for Australia to again stop and consider its options.

“You can’t build any process on that system [the MyHR and CDA]. You can’t even build any reliable analysis on it. These limitations are baked into the design. It doesn’t have to be like this,” he said.

“The MyHR is built on a bunch full of useful infrastructure. There are good ideas in here and it can do good things. It’s just that everything is locked into a single broken solution.

“But we can break it open, and reuse the infrastructure. And the easiest way I can see to do this is flip the push over. That is, instead of the source information providers pushing CDA documents to a single repository, we should get them to put up an Argonaut interface that provides a read/write API [application protocol interface – a key by which all other software and app developers can easily access the system and use the data inside] to the patient’s data.

“What this does is open up the system to all sorts of innovation, the most important of which is that the patient can authorise their care providers to exchange information directly, and building working clinically functioning systems (eg, GP/local hospital, or coordinated care planning).”

Grieve is an unusually strong position to be throwing down this gauntlet to the government and the ADHA. Although he was removed from the MyHR project in Australia, overseas he has emerged as a poster child of solving the interoperability crisis in the US. Feted by nearly all the major global EMR vendors, on speed dial with the some of the most influential people in the US government on health, internationally, he is already a bit of a superstar.

But not your average tech superstar. Although blunt, he’s unassuming, softly spoken, sometimes humble, and is always looking to acknowledge everyone who has helped in the development of FHIR. He sold the rights to FHIR to the HL7 global standards group for nothing, wanting it to be as free and open to use as possible.

He’s driven by his passion to make things as good as they can be, not by fame, money or any of the other things you will sometimes see in someone who attains his status.

He heralds from that village of people who started Linux, Apache, MySQL, and other industry-altering open-source technology, which, as a movement, aims to distribute the power of technology and software, not concentrate it with big global brands or governments.

Compared with his overseas status and the awe with which major global health tech vendors view his work, Australia has treated Grieve almost with disdain.

He did work for the ADHA following on from his work in NEHTA. But his contract with the ADHA was suddenly terminated without explanation.

At the same time, many others who held the views of Grieve were also exited from the ADHA.

It looked at the time like an attempt to own and control the narrative on digital health in the country. The ADHA was going with CDA and a central repository, so having Grieve around was likely seen as a risk to harmony and the narrative being sold to the politicians and the public.

If you talk to certain people in the ADHA they will still try to paint him as an impractical tech zealot.

But Grieve is back in Thessaly. And he has a golden fleece – FHIR – and a lot of narrative power in the support and backing from the giant global EMR vendors. That’s got to be a worry for the ADHA because they can’t just ignore him, FHIR, Argonaut, Cerner, other big EMR vendors, and hope things will go away.

Grieve is positive and maintains that the ADHA, the MyHR and FHIR are still in our possible digital healthcare future. And he wants to go there.

Tim Kelsey, who runs the ADHA, maintains steadfastly that the ADHA is a facilitator organisation, not a control centre. And that it is agile.

But is it agile enough to at least revisit Grieve’s view on the world? Or to at least break bread and see where the middle ground might be?