GPs are in a unique position to support junior doctors who face sexual abuse, says Professor Louise Stone

Back in 2014, Associate Professor Louise Stone looked after a junior doctor who had been sexually assaulted by a colleague. The junior doctor had been raped by her supervisor while she was waiting in a carpark.

The therapeutic relationship immediately felt very different.

“It took me, honestly, 40 minutes to get her to look me in the eye,” Professor Stone said at the inaugural GPs Down Under conference held on the Gold Coast last month.

“After all, she’s a doctor, I’m a doctor … How do I actually be that person in the room when I’m so ashamed of my profession?”

But when Professor Stone went to consult the medical literature on the issue, she found that there wasn’t any.

The experience inspired Professor Stone to start a research project of her own. She conducted a series of in-depth interviews with six female doctors who had been sexually assaulted by male colleagues.

Three of these women, whom Professor Stone calls Stephanie, Claire and Emily, won cases in the criminal or civil courts against the perpetrators, but essentially lost their careers.

“The three other women, whom I call Kate, Alice and Helena all left hospital, did not report [the assaults] and they all ended up in general practice,” Professor Stone said.

One disturbing theme that ran through the interviews was a sense of self-blame.

“When I talked to Alice and Kate they both reflected back and said, ‘Maybe I shouldn’t have been as open and friendly’,” Dr Stone said.

“Helena’s comment was, ‘Maybe I should have been more professional and not smiled as much’, which I think is quite sad.”

Some of the victims almost expected and normalised the abuse, saying that sex with nurses and patients was considered off limits but that junior doctors were regarded as “fair game”.

In many cases, the close relationship the victim had with their mentor turned out to be a form of predatory grooming. Stephanie, for example, was on such good terms with an eminent Sydney radiation oncologist that it did not seem odd when he invited her to his home to discuss a fellowship opportunity.

Stephanie had her drink spiked with a tranquilliser and was indecently assaulted by the oncologist, who later pleaded guilty to the offence.

Another common thread was the ongoing trauma inflicted by drawn out court proceedings, which often forced the victims to remain silent about the assault and continue working with the perpetrator for long periods.

Victims said they did not feel at home in the medical profession following the assault, and often took years to return to work. “These are all profoundly different women based on this experience,” Professor Stone said.

“And I think Stephanie’s impact statement is the most powerful, which says, ‘My world is broken and I will never be the same’.”

The medical profession’s zero tolerance policy around sexual assault did not provide the restorative justice that victims needed, Professor Stone said.

“I’ve been thinking about what happens next,” she said. “We all know this is wrong. We all know this is not acceptable, that we don’t want to be part of this culture.”

The problem is that sexual abuse seems to happen inside hospital communities, where doctors are all embedded in hierarchies and dependent upon each other for career progress.

Female doctors who seek support or make a complaint in this context see their performance scores drop and their careers ruined.

But perhaps general practice could provide a refuge for junior doctors, Professor Stone suggested.

“[That’s the] reason I got into this in the first place; it doesn’t matter what the senior surgeon thinks of me. He doesn’t like me, anyway. I’m ‘just a GP’. I can say this stuff and it doesn’t affect my career.

“We are all in this position. Perhaps we can adopt the junior doctors and give them some safe place to go.”

#GPDU18

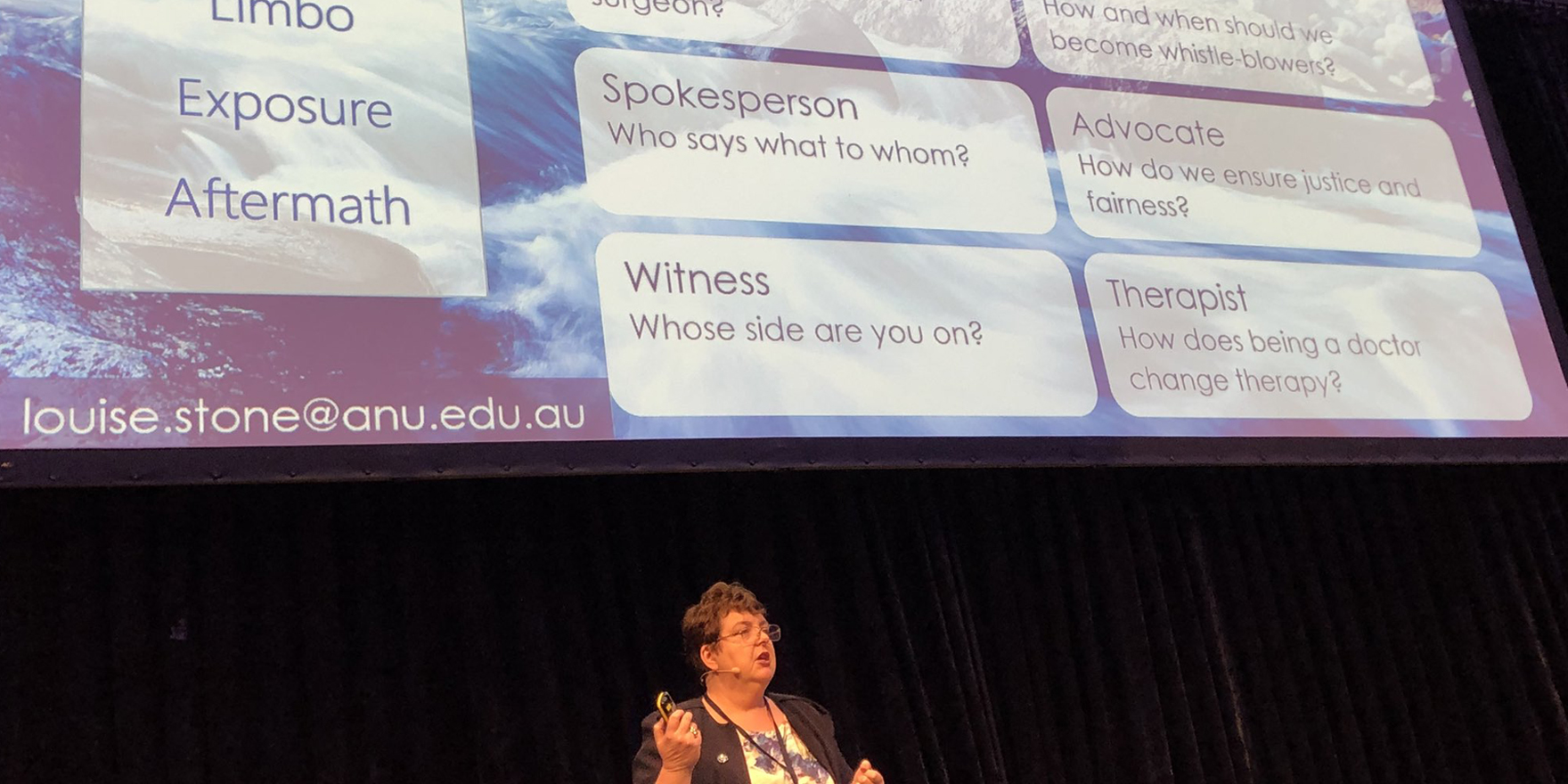

IGNITE with Dr Louise Stone

Hospitals appear to be the unsafe places to be.

Maybe in GP we can be the safe space? pic.twitter.com/Xve8sTwLLK— Todd Cameron (@TcameronTodd) May 31, 2018