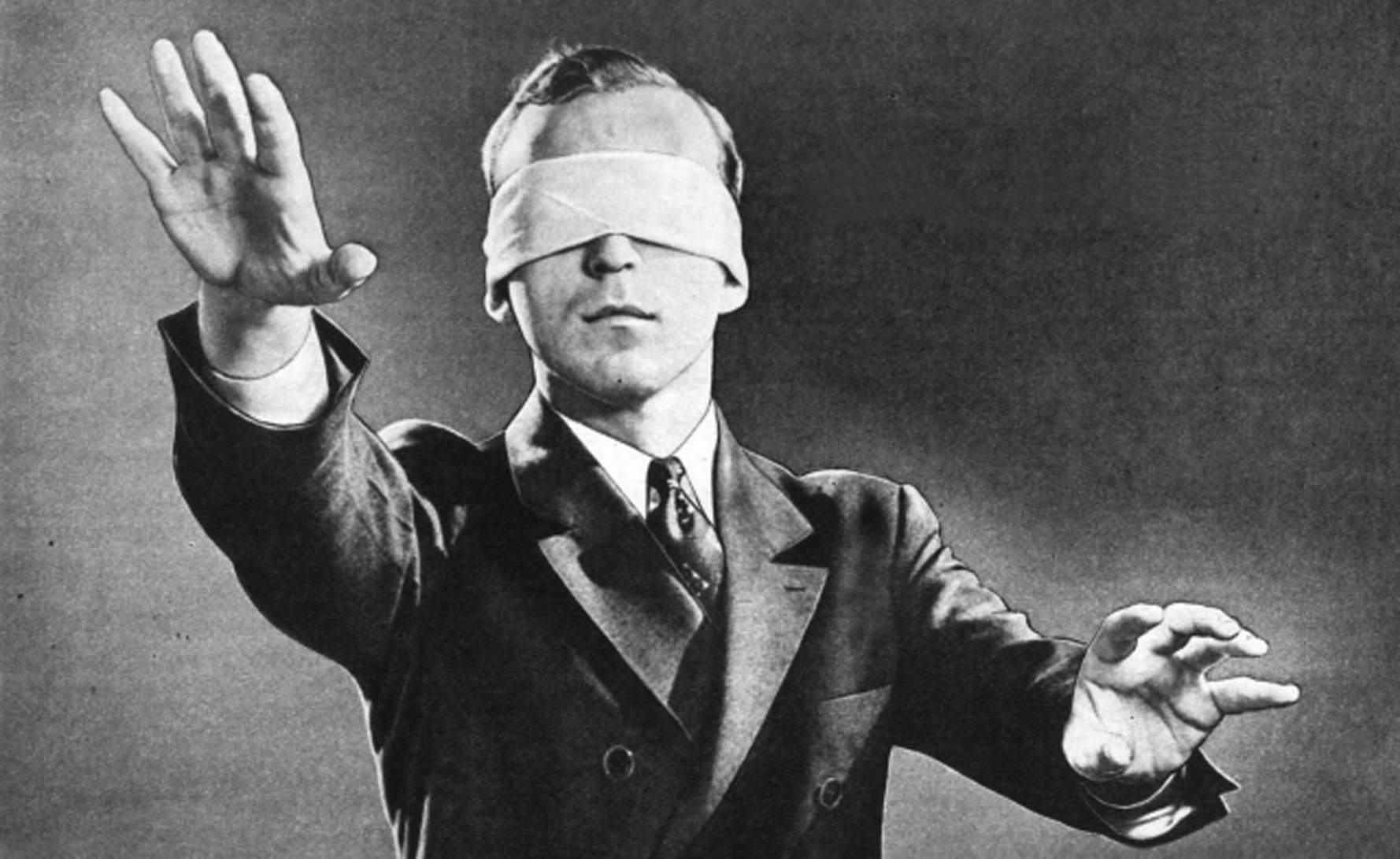

A lack of transparency around hospital complication rates means patients and GPs cannot make informed choices, the Grattan Institute says

Under-reporting of hospital complication rates hides wide discrepancies in care, with the worst hospitals posing four times the risk of the top performers, a report from the Grattan Institute says.

The lack of transparency means patients and GPs cannot make informed choices, and even hospital clinicians are denied information on how their outcomes compare with the rest.

The new Grattan report says one in nine hospital patients in 2012-15 developed a complication in hospital on top of the condition for which they were admitted, affecting about 900,000 people a year. Among those who stayed overnight, the rate went up to one in four, or 725,00 patients annually.

The report calls for state and territory governments, administrators and insurers to release all their detailed data for public and private hospitals, showing the whole range of performance, from rare catastrophic errors to those that are less harmful but prevalent.

“At the moment, a veil of secrecy hangs over which hospitals and clinicians have higher rates of complications and which are safety leaders,” the report says.

“Hospital safety statistics are collected, but they are kept secret, not just from patients but from doctors and hospitals. This has to change.”

The report says patients have a right to know about complication rates in different hospitals and the outcomes for different procedures.

Lead author Dr Stephen Duckett said that, in the absence of hard information, clinicians were inclined to think all was well, unaware of shortfalls in their hospital’s performance.

“It’s something that every clinician should know,” Dr Duckett, the Grattan Institute’s Health Program Director, told The Medical Republic.

“Hospitals need specific information, not average information, so they can drill down and interrogate to make things better,” he said.

The report says if all hospitals could be made as safe as the top 10%, more than a quarter of all complications could be avoided, preventing additional costs, suffering and time spent in care.

“Doctors and hospitals need to know how they are performing compared to their peers, so that they can learn from the best-performing hospitals and clinicians,” the report says.

“The additional risk of a complication at the worst-performing hospitals can be four times higher than at the best performers.”

To compile the report –titled All complications should count: Using our data to make hospitals safer – Grattan Institute researchers analysed de-identified coded hospital data for the period 2012-15, adjusting for risk.

“It is now possible for a hospital to know the rate of complications which occurred for a patient in a given demographic having a given procedure in the past year,” the report says.

“Patients should know that information too, so they can appreciate the risks they face.”

An analysis of cardiac admissions shows the disparity can be substantial.

A patient with an average risk profile in New South Wales faces a 38% higher risk of a complication if they attend the least safe hospital relative to the states’ safest hospitals, the report says.

However, current monitoring does not even attempt to record all the complications that arise in hospitals.

It hinges on eight so-called “sentinel events”, which are very serious, mostly considered to be preventable, and are rare, occurring at a rate of about 100 a year. Since last year, an admission that involves a sentinel event is denied a commonwealth subsidy.

From July this year, penalties will also apply for some of the 16 designated Hospital Acquired Complications (HACs).

Such events – including pressure injury, falls resulting in fracture, and healthcare-associated infections – accounted for just 1.72% of all admissions, according to the report.

The list does not include a multitude of complications that, while less serious, add to the burdens on patients and the health system.

“The focus on a narrow HACS list also means that some hospitals with low HACs rates may be misled into believing they have no scope to improve, when in fact they may have considerable scope to reduce complications not on the HACs list,” the report says.

The authors argue that improvements in patient safety will come by learning from all complications and capturing exceptionally good results as well as average outcomes and causes for concern.

“Many patients are considered high-risk for complications due to the severity of their comorbidities,” they write. “Yet by excluding most complications from transparent reporting practices, we provide insufficient support for clinicians who are striving to achieve better outcomes for these patients.”

The report highlights the fact that a hospital can have a higher rate of complications than its peers, but still have a lower rate than expected given the risk profile of its patients.