GPs are on the frontline for managing patient expectations on medical cannabis, a role only a few feel empowered to play

A landmark survey of Australian general practitioners’ grasp of medicinal cannabis has found what most would freely admit: ignorance reigns.

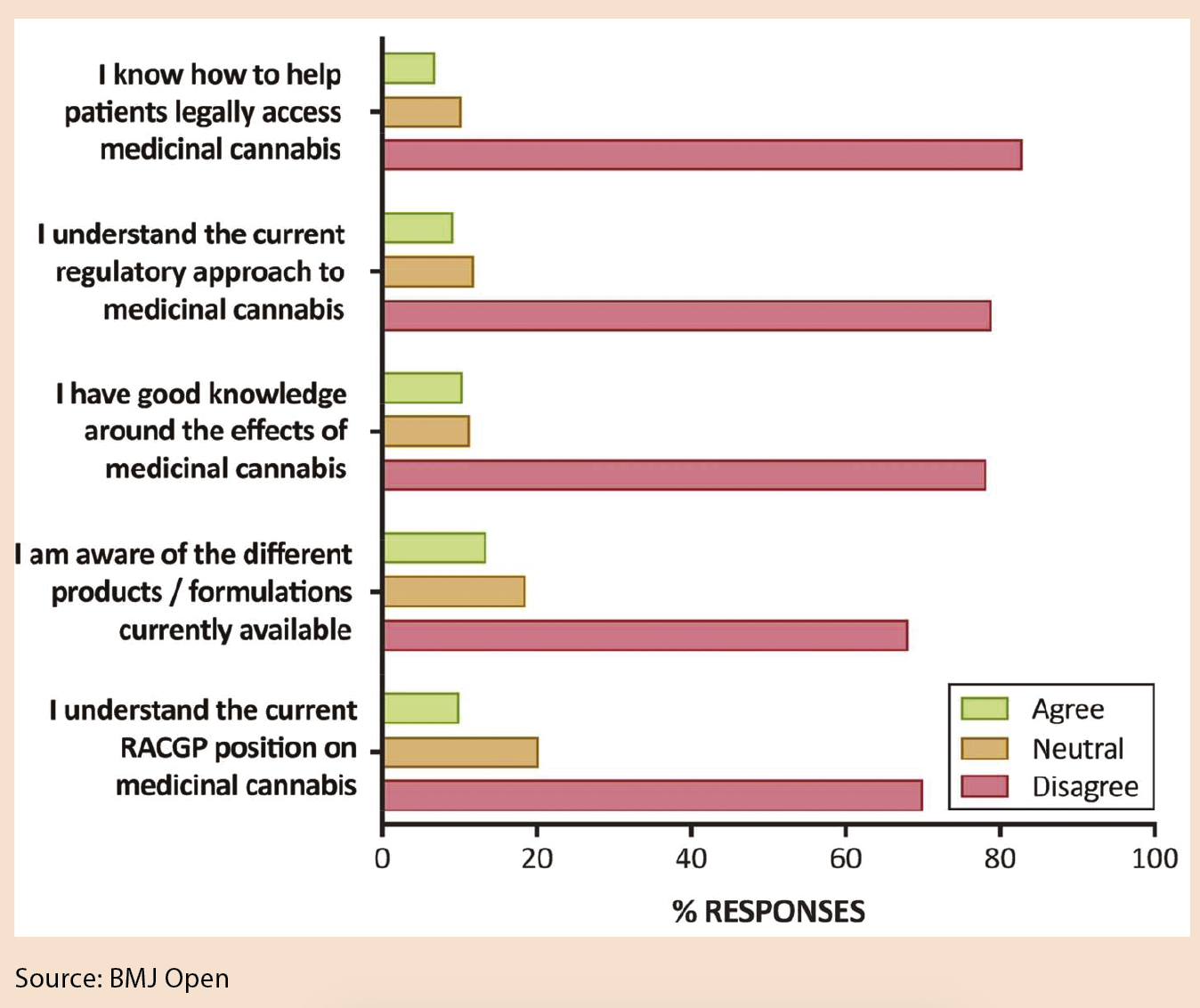

Most of the 640 GPs polled by University of Sydney researchers lacked sufficient knowledge to talk about legal cannabinoid drugs with patients, they said, and couldn’t discuss how to access them nor their effects and potential harms.

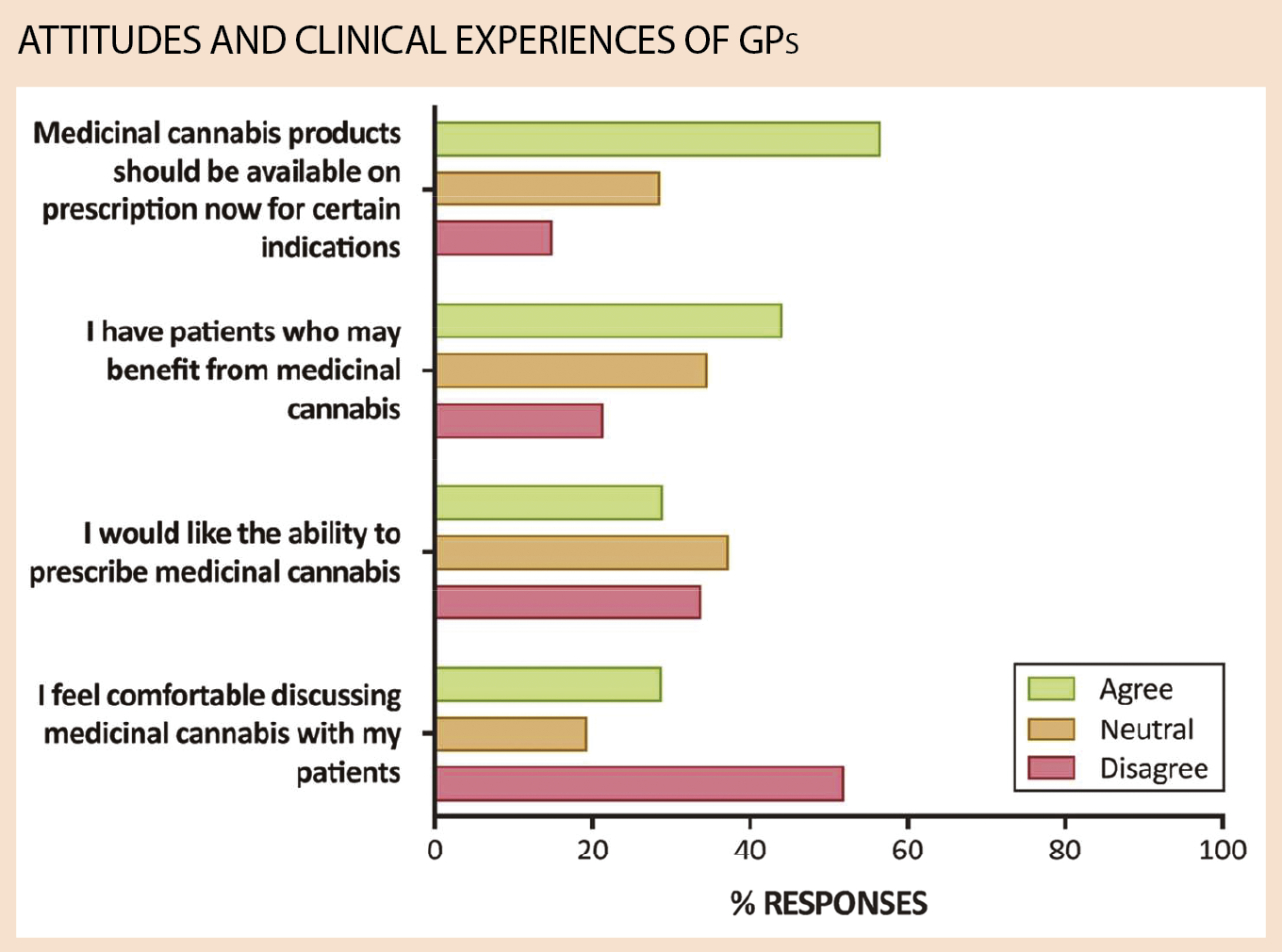

Just over half of respondents nonetheless supported medicinal cannabis on prescription. While that made the cohort more conservative than the general Australian population – which has expressed roughly 85% support – about 30% were agnostic.

The survey results were published by the BMJ Open earlier this month.

GPs self-reported “very low” knowledge: one in 10 understood the current regulatory environment, two-thirds had no idea how to get access for their patients, while four out of five said they did not have good knowledge of its effects.

Only 28.8% felt comfortable discussing medicinal cannabis with patients. And while just 22.8% of respondents felt there was scientific evidence to support the efficacy of medicinal cannabis, half were neutral.

Support was more likely for treatment of chronic cancer pain (80.2% of all respondents) and intractable epilepsy (70.3%) – indications that had a higher evidence base and were also more likely to be supported by state governments, the researchers said.

Concerns centred on abuse and dependence (27.7% would not prescribe medicinal cannabis for this reason), while some GPs worried about repeating the historical mistakes made with opioids and benzodiazepines.

But more than half of GPs with an opinion on whether medicinal cannabis was less hazardous than other prescription medicines thought it was safer than statins and antidepressants, 78.1% thought it safer than chemotherapy drugs, and only one in four thought it more dangerous than opioids and benzodiazepines.

High-profile cannabis researcher and medicinal chemist Professor Iain McGregor, head of the University of Sydney’s Lambert Initiative for Cannabinoid Therapeutics, is corresponding author of the study.

Professor McGregor, who has published more than 50 papers on cannabinoids in the past two decades, told The Medical Republic his team was “surprised and delighted” by the mix of positive and neutral sentiment, which he called “sensible”.

While his organisation was increasingly involved in advocacy and policy work, its “core activity” was developing novel cannabinoid therapeutics, Professor McGregor said.

Lambert Initiative researchers surveyed GPs at one-day seminars in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, and Perth run by GP education company HealthEd between August and September of last year.

A key limitation was that it was a self-selected sample motivated to attend training events and answer a survey.

Professor McGregor told The Medical Republic he had not received funding any from medicinal cannabis drug companies. “They’ve run clinical trials with various products from various companies, but it’s all been at arms’ length.” He said he didn’t own shares or have any commercial interest in the companies involved.

“Everyone acknowledges that the evidence [for medicinal cannabis efficacy] is far from perfect – the historical prohibitions around cannabis have been a major impediment to research. But it’s possible to draw reasonable conclusions with a high degree of confidence in some cases about the effects of medicinal cannabis on certain conditions.”

“You shouldn’t drive when you’re high on a THC preparation and cannabis dependence does exist… but adverse effects are far below those of benzodiazepines and opioids and many other drugs that are just routinely prescribed in clinical practice.”

Professor McGregor estimated around 100,000 Australians used illicit cannabis for medicinal purposes, a back-of-the-envelope calculation based on the number of registered patients in Canada.

About 700 patients have been prescribed cannabinoid drugs in Australia since they were legalised in late 2016, and in May 2018 health officials told a Senate estimates committee there were 33 authorised prescribers here, mostly paediatric neurologists and palliative care doctors.

Nathan [not his real name] is not one of the 700, but considers himself one of the 100,000. The 32-year-old technical and creative worker from Sydney’s inner west had experimented with illicit cannabis for “recreational” and “medicinal” purposes, he said.

While he has smoked cannabis intermittently since his teens, Nathan said nowadays his use was primarily confined to short stints to ease the symptoms of dose changes to his clinically prescribed escitalopram.

“Whenever the dose is adjusted I tend to get really horrible feelings of anxiety for about a week. I feel very physically heightened as well as being mentally foggy. It’s a bad thing to deal with.

“One mid-sized joint in the evening” during these transition times provided relief, he said, contrasting this with his compulsive use several years ago.

“Then I would get back from work every day and immediately start smoking, and smoke upwards of two to three or four joints in an evening, on top of drinking beer and drinking wine, combining different substances – and that would last for months.”

Nathan wasn’t surprised by the survey results. “I’m fortunate enough to be in a position with a GP and a psychotherapist now where I’m able to discuss my use of cannabis in both a recreational and self-medicating form without judgment – but that hasn’t been my overall experience,” he told The Medical Republic.

“It’s the subtleties of these different kinds of experiences that are appreciated by the health professionals that I deal with now.”

But Professor Vicki Kotsirilos, who last month became the first GP in Australia empowered to prescribe medicinal cannabis to her usual patients without TGA approval, had deep concerns about what she considered a blurring of the lines between medicinal and recreational cannabis use.

“There’s very little evidence to suggest [cannabis] is useful for depression, in fact it’s contraindicated,” Professor Kotsirilos said, adding she couldn’t give specific advice for a patient she hadn’t seen.

“The recreational use of illicit cannabis has been proved to be harmful to mental health – particularly in adolescents whilst their brain is developing.”

True medicinal cannabis was a cannabis-derived product in a strict formulation, perhaps in an oral spray or an oil, approved by the TGA and prescribed by a GP or specialist, she said. And it was a last-resort treatment for chronic neuropathic or cancer pain.

Nathan’s experience reveals another issue, though: the financial cost. He spends an estimated $2 to $5 per joint.

Meanwhile, synthesised medicinal cannabis formulations, which are generally imported from the US, might cost a prohibitive $30,000 for a year-long course.

Fewer than 15% of GPs supported the use of cannabis to manage depression and anxiety. But Nathan is quite typical in doing so, as an upcoming community survey of cannabis use by Professor McGregor’s team will show.

MEDIA HYPE DRIVING PATIENT ENQUIRIES

Just over 60% of respondents reported at least one patient enquiry about medicinal cannabis in the three months prior to completing the survey, with some receiving more than five enquiries.

That’s a fraction of the roughly 6000 GP visits per full-time equivalent GP Australians make each year, but Professor McGregor said, anecdotally, enquiries had escalated. “Ongoing media coverage” has fuelled “unrealistic patient expectations,” the researchers wrote.

“This is the terrible dilemma of GPs – that in a way they’re on the frontline dealing with patients’ expectations, but the current system hasn’t really empowered them,” Professor McGregor said.

“They have to deal with patients coming along with [chronic pain unresponsive to] every opioid and gabapentinoid known to mankind, saying ‘none of them have really worked, can I give cannabis a go?’”

The researchers concluded there was an “urgent need” for improved training to overcome the knowledge gap, and also called for more prescribing powers for GPs.

Professor Kotsirilos agreed. “I’m not surprised at all by the knowledge gap. GPs have had very little training in medicinal cannabis and clearly we do need to be training more GPs in the area.”

Only 10% of GPs surveyed said they understood the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners’ position on medicinal cannabis, while 70% did not.

RACGP President Dr Bastian Seidel declined an interview with The Medical Republic, but Professor Kotsirilos, who is also chair of the RACGP’s Australasian Integrative Medicine Association Joint Working Party, said the finding surprised her.

“The RACGP has been quite active in communicating with its members through its media releases and through [its website] about its position on medicinal cannabis,” Professor Kotsirilos said.

“The cohort of GPs who were surveyed may not be RACGP members.”

She said the access system was still “too bureaucratic” and the college was advocating for its “simplification and streamlining”, and for “GPs to be treated like other specialists, and to have the autonomy of prescribing medicinal cannabis when we feel like it’s appropriate for the condition with which the patient presents.”

GPs are currently able to become authorised prescribers after applying to the ethics committee of the Melbourne-based National Institute of Integrative Medicine (NIIM).

LEADING ROLE FOR GPs

Despite poor knowledge and reservations about efficacy, almost four in five respondents backed a GP-led access model, while three in five supported a model that shared care with specialists, and 44.6% supported specialist-only prescribing.

A question added later in the survey (n=398) which asked GPs to select their preferred model saw 41.2% choose trained GP-only, 29.6% “shared care” and 14.6% specialist-only prescribing.

Professor McGregor guessed this was because specialists, led by the Australian College of Physicians, had been relatively conservative on the issue. He also pointed to cost and access issues around specialists, and suggested professional resentment might play a role.

“I think there’s a certain level of resentment there that [GPs] are entrusted with potentially far more hazardous or lethal drugs yet they’re not entrusted with medicinal cannabis,” Professor McGregor said.

“That somehow you need to be a specialist in order to handle that one, even though nobody ever died of a cannabis overdose, and 50,000 people died in the US of opioid overdoses last year, he said.

The day McGregor’s survey was published saw the simultaneous release of a large and widely reported Lancet Public Health study which found no clear evidence opioid users in chronic pain found relief from illicit cannabis. Many seized on the study to rebuke medicinal cannabis. But Professor McGregor said he considered it “hazardous and premature to use studies like this to conclude that medicinal cannabis is ineffective in treating non-cancer pain”.

It was an observational study conducted primarily by phone interview self-report, he pointed out, “with no control over cannabis administration, formulation or dosing in patients” and no independent verification of either pain levels or cannabis use.

“When these sort of studies are used to show positive effects of medicinal cannabis, they are invariably criticised as being severely methodologically flawed,” he said.

References:

1. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/8/7/e022101.info

2. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanpub/article/PIIS2468-2667(18)30110-5/fulltext