Logic would dictate there would need to be considerable evidence for serious harm from vaping to deny access to smokers, writes Dr Colin Mendelsohn

A recent report from the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (RACP) acknowledging that personal vaporisers (e-cigarettes) can help smokers quit is a welcome change. (1) Nevertheless, the College still continues to oppose their use because of concerns about potential risks.

The College recommendation is in direct conflict with a comprehensive report by the highly respected UK Royal College of Physicians (2) which found that vaping has “huge potential to prevent death and disability”, notwithstanding some potential risks. The UK experts recommend that “in the interests of public health it is important to promote the use of e-cigarettes … as widely as possible as a substitute for smoking”.

Only one of these colleges can be right.

Vaporisers are indeed effective and millions of smokers have quit overseas by switching to vaping. (3) Large population studies have shown that daily use increases quit rates by between three to eight times that of other methods used.(5)

The limited randomised controlled trials so far have found that vaping with early, now-obsolete devices doubled the likelihood of quitting. (6) Contemporary devices are more effective, deliver higher doses of nicotine and have higher quit rates. (7)

It is no surprise that vaporisers are the most popular quitting aid in the United Kingdom, (8) the United States (9) and the European Union.

Logic would dictate that there would need to be considerable evidence for serious harm from vaping to deny Australian smokers access to this lifesaving technology.

However, the RACP opposition is based on exaggerated fears and uncertainties rather than solid evidence – fear that vaping will lead young people to smoke, fear that it will renormalise smoking and fear of unknown long-term health effects. These concerns are legitimate but are not supported by the available evidence.

The RACP is concerned that young non-smokers will become regular vapers and progress to smoking. However, international evidence shows this is not happening.

Regular vaping by young people is rare and is almost exclusively confined to current smokers. In large studies in the United States (10) and United Kingdom (11) <0.5% of teens who have never smoked were vaping regularly and there is very little evidence of progression to smoking. (12)

Numerous national studies show that regular vapers are almost exclusively ex-smokers or smokers.

The evidence suggests that vaping is replacing – rather than encouraging – smoking of tobacco cigarettes among young people and is reducing smoking uptake. (13)

If vaping is a gateway from vaping into smoking, it is likely to be very small indeed and is swamped by the much larger gateway out of smoking. (14)

There is a theoretical argument that the greater visibility of vaping will make smoking appear more socially acceptable and increase its uptake. However, research so far suggests the opposite is happening.

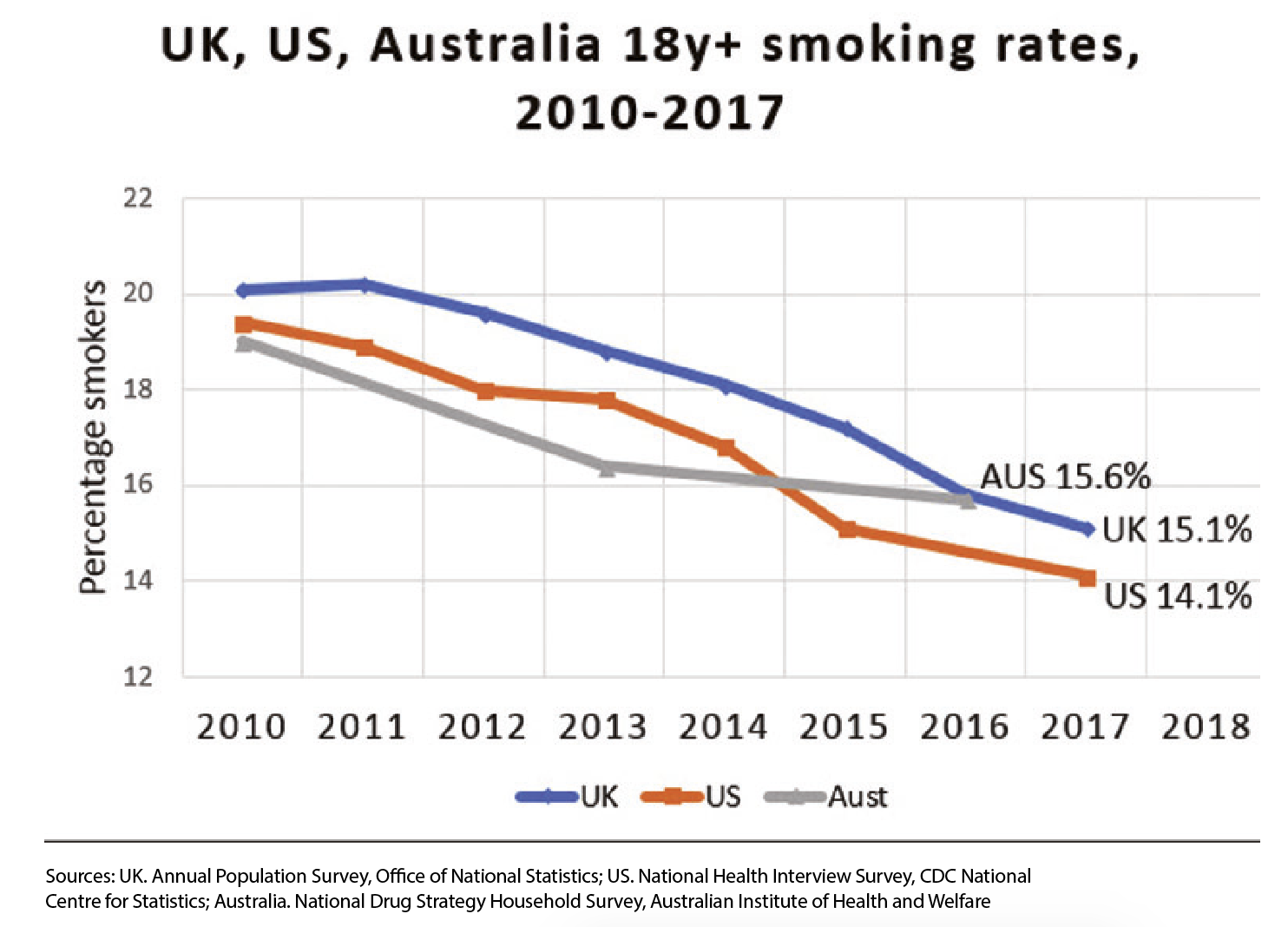

Rather than rising, smoking rates are falling rapidly in many countries where nicotine vaporisers are legal and widely available, as shown in the above table. However, in Australia, where vaping is banned, smoking rates have stalled since 2013 (15) and have recently increased significantly in NSW. (16)

Furthermore, the uptake of vaping by non-smoking adults is rare. Where vaping is available, uptake by adult non-smokers is <0.5% in most national surveys. (17)

Nothing is entirely risk-free, but the growing evidence so far indicates that long-term vaping is likely to be much safer than smoking. The UK Royal College of Physicians (2) reviewed the evidence and concluded that long-term vaping is at least 95% less harmful than smoking.

This is because the vast majority of the 7,000 chemicals and toxins in smoke are generated by the burning of tobacco leaf. Vaping involves heating a nicotine liquid solution. There is no combustion, tobacco or smoke and almost all of the toxins in smoke are either absent from vapour or are below harmful levels. (18)

The evidence so far indicates that smokers who switch to vaping have substantial health improvements, for example in COPD (19) and hypertension. (20)

The RACP has based its position on exaggerated uncertainties and unproven fears about vaping and has ignored the huge potential public health benefit. In doing so it has failed Australian smokers.

If we wait 30 years until we have the definitive proof the College wants, many people will die unnecessarily. Up to two out of three Australian smokers are killed by their habit if they continue to smoke. (21)

The reality is that many smokers are unable or unwilling to quit with conventional therapies. For these smokers, we should be making it easier to switch from a high-risk to a lower-risk nicotine product, not harder, while introducing even more effective strategies to reduce youth initiation.

The RACP is arguably risking the lives of smokers if doctors and smokers follow its advice.

Dr Colin Mendelsohn is an Associate Professor and Chairman of The School of Public Health and Community Medicine, University of New South Wales, Sydney

For more information about tobacco harm reduction and vaping, please go to:

www.athra.org.au

References:

Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Policy on e-cigarettes. May 2018. Available at: https://www.racp.edu.au/docs/default-source/advocacy-library/policy-on-electronic-cigarettes.pdf Accessed 24 June 2018

- Royal College of Physicians. Nicotine without smoke: Tobacco harm reduction. London: RCP. 2016. Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/nicotine-without-smoke-tobacco-harm-reduction-0 Accessed 24 June 2018

- Farsalinos KE, Poulas K, Voudris V, Le Houezec J. Electronic cigarette use in the European Union: analysis of a representative sample of 27 460 Europeans from 28 countries. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2016;111(11):2032-40.

- Giovenco DP, Delnevo CD. Prevalence of population smoking cessation by electronic cigarette use status in a national sample of recent smokers. Addictive behaviors. 2017;76:129-34.

- Berry KM, Reynolds LM, Collins JM, Siegel MB, Fetterman JL, Hamburg NM, et al. E-cigarette initiation and associated changes in smoking cessation and reduction: the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study, 2013-2015. Tobacco control. 2018.

- Royal College of Physicians. Hiding in plain sight: Treating tobacco dependency in the NHS. 2018. Available at: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/hiding-plain-sight-treating-tobacco-dependency-nhs Accessed: 23 July 2018

- Hitchman SC, Brose LS, Brown J, Robson D, McNeill A. Associations Between E-Cigarette Type, Frequency of Use, and Quitting Smoking: Findings From a Longitudinal Online Panel Survey in Great Britain. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2015;17(10):1187-94.

- West R, Brown J. Smoking Toolkit Study. Smoking in England 2018. Available at: www.smokinginengland.info/latest-statistics/. Accessed 15 May 2018

- Caraballo RS, Shafer PR, Patel D, Davis KC, McAfee TA. Quit Methods Used by US Adult Cigarette Smokers, 2014-2016. Preventing chronic disease. 2017;14:E32.

- Farsalinos K, Tomaselli V, Polosa R. Frequency of Use and Smoking Status of U.S. Adolescent E-Cigarette Users in 2015. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54(6):814-20.

- Bauld L, MacKintosh AM, Eastwood B, Ford A, Moore G, Dockrell M, et al. Young People’s Use of E-Cigarettes across the United Kingdom: Findings from Five Surveys 2015-2017. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2017;14(9).

- National Institute on Drug Abuse – National Institutes of Health. National Survey Results on Drug Use 2017. Available from: http://monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2017.pdf.

- O’Leary R, MacDonald M, Stockwell T, Reist D. Clearing the Air: A systematic review on the harms and benefits of e-cigarettes and vapour devices. University of Victoria, BC: Centre for Addictions Research of BC.; 2017. Available at: http://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/carbc/assets/docs/report-clearing-the-air-review-exec-summary.pdf Access date 1 July 2017

- Warner KE, Mendez D. E-cigarettes: Comparing the Possible Risks of Increasing Smoking Initiation with the Potential Benefits of Increasing Smoking Cessation. Nicotine & tobacco research : official journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco. 2018.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. National Drug Strategy Household Survey (NDSHS) 2016: detailed findings. Drug Statistics series no. 31. Cat. no. PHE 214. Canberra: AIHW, 2017. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/15db8c15-7062-4cde-bfa4-3c2079f30af3/21028.pdf.aspx?inline=true. Accessed 24 June 2018

- HealthStats NSW. Health Statistics NSW. NSW Ministry of Health, 2018. Available at: http://www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/. Accessed: 23 July 2018

- McNeill A, Brose LS, Calder R, Bauld L, Robson D. Evidence review of e-cigarettes and heated tobacco products 2018. A report commissioned by Public Health England. London: Public Health England. 2018. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-and-heated-tobacco-products-evidence-review Accessed 4 April 2018

- Farsalinos KE, Poulas K, Voudris V, Le Houezec J. Prevalence and correlates of current daily use of electronic cigarettes in the European Union: analysis of the 2014 Eurobarometer survey. Internal and emergency medicine. 2017.

- McNeill A, Hajek P. Underpinning evidence for the estimate that e-cigarette use is around 95% safer than smoking: authors’ note. PHE publications gateway: 2015260. 2015. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/e-cigarettes-an-evidence-update (11 October 2015)

- Polosa R, Morjaria JB, Caponnetto P, Prosperini U, Russo C, Pennisi A, et al. Evidence for harm reduction in COPD smokers who switch to electronic cigarettes. Respiratory research. 2016;17(1):166.

- Farsalinos K, Cibella F, Caponnetto P, Campagna D, Morjaria JB, Battaglia E, et al. Effect of continuous smoking reduction and abstinence on blood pressure and heart rate in smokers switching to electronic cigarettes. Internal and emergency medicine. 2016;11(1):85-94.

- Banks E, Joshy G, Weber MF, Liu B, Grenfell R, Egger S, et al. Tobacco smoking and all-cause mortality in a large Australian cohort study: findings from a mature epidemic with current low smoking prevalence. BMC medicine. 2015;13:38.