The damage caused by infectious disease in older people is largely preventable, so why is there so little faith in adult vaccines?

When researchers ask older people “Why didn’t you get vaccinated?” the most common answer is “My doctor never told me”, epidemiologist Professor Raina MacIntyre says.

Australians jump up and down if childhood vaccination coverage drops below 90%, Professor MacIntyre told the Adult Immunisation Forum in Melbourne last month.

But when it comes to communicable disease prevention in older people, we just shrug our shoulders.

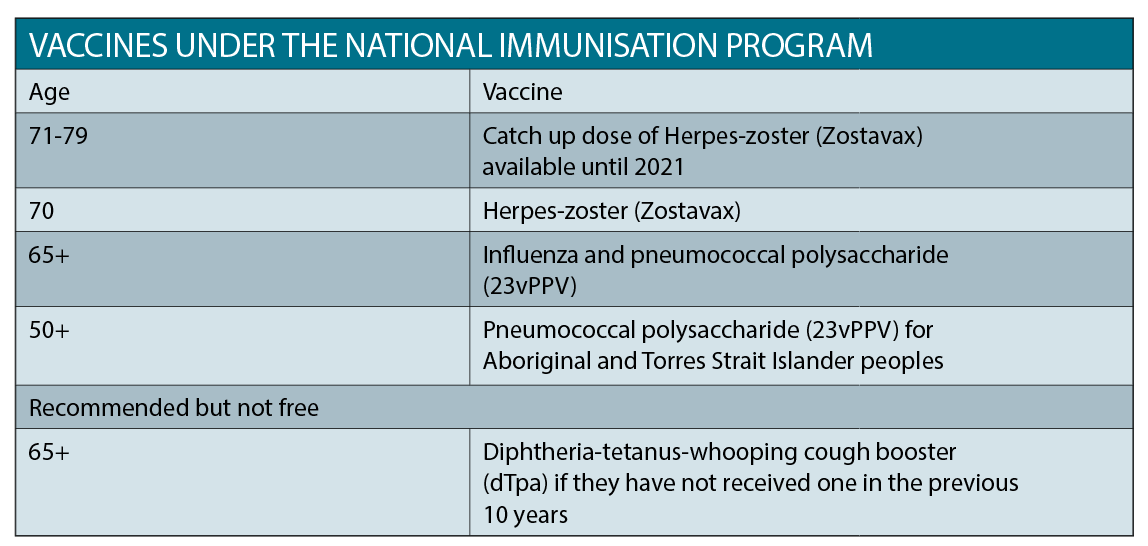

For example, coverage rates for influenza sit around the 75% mark for adults aged 65 and over.1 And just over half of people in this category are inoculated against pneumococcal disease. Yet both of these vaccines are free to older people under the National Immunisation Program. Alarmingly, only 12% of adults aged 18 and older have received a recent pertussis vaccination.

People with dementia, and those aged over 80, are the most likely to be under-vaccinated for pneumococcal disease,2 despite being perfectly capable of a robust immune response.3

Some nursing home staff also are not immunised. “And yet we know that we get these explosive outbreaks in aged-care facilities,” says Professor MacIntyre, the head of the School of Public Health and Community Medicine at UNSW.

Apples and oranges

So why are we happy to accept low vaccination rates in older people?

“Research shows that doctors and providers are less convinced about vaccines for the elderly,” says Professor MacIntyre. Doctors simply do not advocate as strongly for vaccination in older people as they do for children.

Immunising infants has big rewards as each vaccine is given on the background of a progressively strengthening immune system, says Professor MacIntyre. But the opposite is true in older people; the immune system declines from the age of 50.

Immunosenescence describes the lowering of immune defences during the ageing process. The body produces fewer, and more-defective, antigen-presenting cells, such as plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Cytokine production is impaired, the action of T cells is altered, and the function and diversity of B cells is diminished.

All this leaves older people more susceptible to infectious diseases.

It also means the effectiveness of vaccines, or immunogenicity, diminishes in seniors. Vaccinations in older patients are often seen as a “losing game”, says Professor MacIntyre. “And this is what we need to change our thinking about.”

The frail elderly, and older people with co-morbidities, are systematically excluded from randomised controlled trials. “This exclusion results in a vicious cycle of lack of evidence, lack of recommendation, and lack of protection for the oldest and frailest people in society,” says Professor MacIntyre.

Compounding this, paediatricians are over-represented in most of the peak advisory bodies for immunisation in Australia. “So you have fewer champions for adult immunisation at the level where it matters, where policy is made,” she says.

Stronger advocacy for adult immunisations is important if the recently launched Australian Immunisation Register is to fully realise its promise of recording vaccines given to people of all ages. “It is still yet to be determined exactly how the data captured in the register can be used,” says Professor MacIntyre.

“We don’t know yet whether a GP can access the data and see whether the patient in front of them has been vaccinated.”

Doing the maths

Vaccines are considered “pretty hopeless” if their efficacy falls below 60%, says Professor MacIntyre, despite many universally accepted preventative medications having similar success rates.

For instance, the efficacy of the influenza vaccine drops to about 27% to 40% in the elderly, but statins are only around 25% effective for secondary prevention. In people over 65 years, the influenza vaccine cuts hospitalisations by 37%.

In addition, the flu shot has been linked to a significantly lower rate of heart attacks in people with ischaemic heart disease.

Some studies show that older people who are vaccinated against influenza experience less severe symptoms if they do get sick, says epidemiologist Professor Paul Van Buynder, chairman of the Immunisation Coalition. “You got the flu, but you weren’t hospitalised and you didn’t die.”

What is often forgotten when considering the value of vaccinations in older people is that: Public health benefit = efficacy of the vaccine x burden of disease.

This means it is still be worth vaccinating older people for common diseases, even if the vaccine efficacy is relatively low. For example, if there are 100,000 cases of disease among people aged 75 to 84 years, and 50,000 cases in people aged 65 to 74 years, then vaccinating the younger age group (70% efficacy) will prevent 35,000 cases, but vaccinating the older age group with a vaccine that loses efficacy (50% efficacy) would prevent 50,000 cases.4

Value judgments

The phrase “pneumonia is an old man’s friend” sums up the entrenched ageism that perpetuates vaccine inequities in Australia, says Professor MacIntyre.

“To me, ‘pneumonia is an old man’s friend’ means ‘old people are a burden and should hurry up and die’,” she says.

This kind of thinking strips older people of their right to autonomy, and dismisses their suffering.

Research shows that nurses and doctors tend to prioritise younger patients and often withhold treatment, prevention or information from older patients.5 In the case of vaccination, these value judgments lead to increased morbidity, death and the spread of disease, and are in no way ethically justifiable, says Professor MacIntyre.

Healthy ageing should be a priority for public health, Professor MacIntyre argues, particularly as 25% of the population in developing nations will be over 65 by the middle of this century.

Patient attitudes

Older people are often willing to risk of getting sick to avoid the minor inconveniences associated with vaccination. Only around 50% of older people have been vaccinated against shingles since Zostavax was made available for free for Australians aged 70 (with a catch up for those aged 71-79) in November last year.

Dr John Litt, a GP academic, and formerly an associate professor at Flinders University, examined why this might be the case.

His research shows that people are less likely to be vaccinated for herpes zoster if they:

• believe their risk of getting sick is low

• don’t think the disease is severe

• don’t have a usual GP

• are relatively healthy

• believe in natural immunity

• are concerned about adverse events, particularly allergic reaction

• did not have a GP discuss vaccination with them

Only around 7% of patients said they did not trust their GP. In this cohort, only one-third were vaccinated for zoster following a GP visit.

Around 32% were unsure or believed that natural immunity was superior. But, once given a GP recommendation, 64% of these people got a zoster vaccination. By comparison, 92% of patients who believed vaccines would improve their immunity accepted the zoster vaccine after a GP recommendation.

After adjusting for all other factors, patients were 10 times more likely to be vaccinated if a GP recommended immunisation.

“Around 55% of older people said they would get the zoster vaccine before it went on the market,” according to Dr Litt.

“If your GP recommended it, that went up about 89%.”

A two-fold strategy is needed to raise vaccine coverage to 100%, says Dr Litt.

“It is not just a matter of the GP suggesting to the patient that they need to get a vaccine, you actually need to think about the specific attitudes.”

Invisible threat

People are often unaware of the potentially devastating effects of infectious disease, particularly if they haven’t heard about the illness first hand from friends or family.

Few would realise that influenza is the third leading cause of “catastrophic disability” in frail older people, behind stroke and congestive heart failure, says Professor Buynder.

Patients may also not be aware that the pain associated with shingles can last for over a year in almost half of patients aged 79 or over.

Few would know that a recent study of half a million patients published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology found that shingles increased the risk of stroke by 35% and the risk of heart attack by 59%.6

Whooping cough can also be hugely debilitating. A recent study of 70 adults with pertussis by Associate Professor Bette Liu, an epidemiologist at UNSW, showed that more than two-thirds reported being unwell for more than 15 days.

“There is some substantial morbidity from pertussis that really isn’t recognised,” says Professor Liu.

Such impacts suggest clearer communication of exactly what horrors vaccines prevent, could go a long way towards improving vaccination rates in older people.

References:

1. 2009 Adult Vaccination Survey, March 2011, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare

2. Hum Vaccin. 2007 May-Jun;3(3):83-6.

3. PLoS One. 2014 Apr 23;9(4):e94578.

4. Health 5 (2013) 80-85

5. Health Care Anal. 2014 Jun;22(2):192-201.

6. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2017, online 3 July